Gin: or the ‘demon’ redeemed

Author: Berry Bros. & Rudd

The drunkard sunk more in disgrace, / Had a look of brutality scowling; / In his soul, in his heart, in his face, / The gin like a demon was howling. – From a popular song of the early 19th century

Most drinks can be presented in a historical setting of some distinction, even lustre. Sherry has its stories of Old Spain and merry quaffers of “Sack”; Rum, its yarns of buccaneers and years before the mast; Whisky, its stirring glimpses of swinging kilts and skirling pipes. Not so Gin, however. In this case, the story has to begin in surroundings of squalor, misery and degradation, amongst the London Poor of the eighteenth century. If Gin has acquired today a comfortable air of respectability (even to the extent of being prescribed under the National Health Service), it has done so by living down a past of ill fame never equalled in the history of drinking.

Gin entered English life at a time when – for the humbler citizens of the capital at least – it was at its bitterest. The ordered pattern of medieval and Tudor society had broken down, and the social conscience of the 19th century had not yet been born. For the first time, “the poor” were really with us: the poor as a dispossessed and despised section of the population crowded into the filthy hovels and rookeries that made a social “plague-spot” of the London of George II. Working hours were long (from six in the morning to eight or even nine at night), prices high and holidays few apart from the public “hanging days” at Tyburn. For those who survived epidemics and under-nourishment, there were the hazards of ill-lighted and ill-policed streets… highwaymen and thugs, naval pressgangs and kidnappers of labour for the American plantations, the wiles and importunities of prostitutes and pimps. As Gay saw it in 1717:

O may the virtue guard thee thro’ the roads / Of Drury’s mazy courts and dark abodes!

It was to this cowed and brutalised populace that the new solace came in the form of Gin – cheap, abundant, potent Gin. The days were by now far distant when French and Rhenish wines had filled the flowing bowl, and Ale had been for generations the backbone of England. Whether the scene of prosperity and sober enjoyment depicted in Hogarth’s Beer Street (in which he sought to contrast the good effects of Ale with the evils of Gin) was the typical accompaniment of the traditional tipple may be doubted, for in 1722 his countrymen had succeeded in drinking a quantity of beer equivalent to a 36-gallon barrel for each man, woman and child of the population. But whatever the damage done by excessive beer-drinking, it was nothing to what was to follow when the gin-shops put out their notorious invitation: “Drunk for a penny. Dead drunk for twopence. Clean straw for nothing.”

With higher home production and consumption of spirits in political favour as a “patriotic” move to use corn and help the landowners, the gin distillers set to work encouraged by a tax so light that even the poorest could become their customers. Meanwhile, the retailing of the spirit was virtually thrown open to all and sundry. Unlicensed “dram-shops” began to open by the hundred and thousand, until by 1733 there were between 6,000 and 7,000 in London alone – a London in which St. James’s Street lay on the south-western outskirts and the village of “Chelsey” was an afternoon’s excursion up-river.

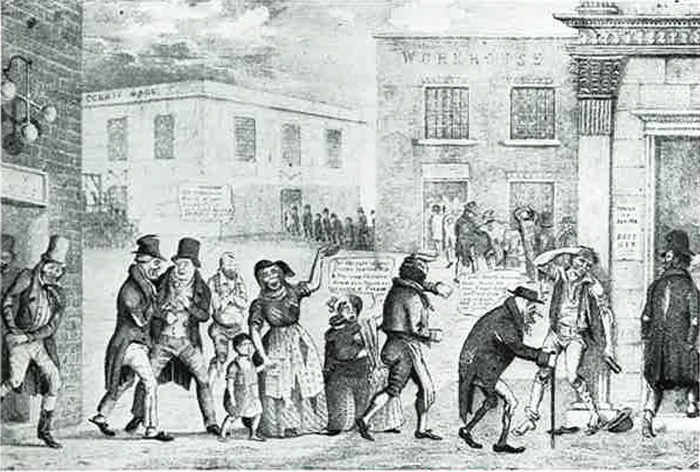

The Drunkard’s Progress: From the Pawnbroker’s to the Gin Shop, from thence to the Workhouse, thence to the Gaol and ultimately to the Scaffold. An early 19th century comment on the Gin-drinking “fever”.

Gin-drinking spread like an epidemic. In 1734, George II’s subjects poured nearly 5,000,000 gallons down their throats; and by 1742, despite half-hearted attempts by the Government to control the traffic, this figure had risen to well over 7,000,000 gallons. Even workmen’s wages were often paid in the form of cheap Gin. With it came those scenes of drunkenness, brutality, crime and degradation epitomised by Hogarth in his Gin Lane. As depicted by the illustration on page 15 [above], the path of Gin ran “from the Pawnbroker’s to the Gin Shop, from thence to the Workhouse, thence to the Gaol and ultimately to the Scaffold.” One way or another, it led to an early grave. The death-rate rose alarmingly, and between 1740 and 1742, when the Gin fever was at its height, there were twice as many burials as baptisms in the London area. Even after 1751, when the Government finally took decisive action to check the traffic, medical men attributed one-eighth of all adult deaths in London to excessive spirit-drinking.

It was public pressure that drove Parliament in 1751 to go beyond the hesitating steps previously taken to stop the rot. Shocked by the revelations of Fielding’s Inquiry into late Increase of Robberies &c., and still more by Hogarth’s savage delineation of the horrors of gin-drinking, the nation expressed its revulsion in a flood of petitions from all sides. As a result, effective legislation was at last introduced to stop illicit sales of cheap spirit and control output and consumption. By the end of George II’s reign, although dram-drinking was still rife, the habit had been brought back within reasonable bounds.

But that was far from being the end of Gin’s sorry social record. With the Industrial Revolution, and the reinforcement of the ranks of the poor by the new “working classes”, spirit-drinking regained its hold at the beginning of the 19th century as the easiest and cheapest way of forgetting life’s burdens and sorrows. Its perils were exposed in such popular songs as The Bottle (“A Celebrated Song written by James Bruton and sung by Mr. J. W. Sharp with Universal Applause”), which told of the downfall of Sam Swill and his family:

Of Bedlam at last he’s the guest, / And near him two children gather, / His children – in low flash clothes drest / To gaze at their maniac father!

Such cautionary tales notwithstanding, Gin continued to add to the number of its votaries. Creevey refers to a falling-off by nearly half between corresponding periods of 1826 and 1827 in the sales of Barclay’s beer and Ale – “entirely owing to Mr. Huskisson’s policy in taking off the duty upon Gin, which is now so cheap that a whole family may and do get drunk with it for a shilling.” Magistrates in Surrey, he adds, are “horrified with the increase of Gin drinking and crime during the last year.”

Cruikshank gives us his picture of the ravages of Gin and its allies in such fierce caricatures as The Drunkard’s Children and The Bottle. Dickens surrounds that “performer of nameless offices about the persons of the dead,” Mrs. Gamp, with a “smell of spirits” that must have been very characteristic of her kind in real life, and into her mouth puts a remark that could well serve as the plea of her gin-addicted generation – and, indeed, of alcoholics of all time. “If it wasn’t for the nerve a little sip of liquor gives me… I never could go through with what I sometimes has to do.”

Not until the latter part of Queen Victoria’s reign, through the combined influence of the Salvation Army, the “Blue Ribbon Army” (a sort of Alcoholics Anonymous of its day), the spread of education and more varied social amenities, did Gin begin to shake free of its nefarious associations and take its place in polite society as something to be enjoyed in moderation.

Gin and Mrs. Gamp. From the drawing of Fred Barnard, who illustrated the Household Edition of Dickens’s Works in the 1870s. Illustration: Hulton Picture Library.

Gin derives its name from jenever, the Dutch word for juniper, the berries of which are used in flavouring the spirit. Genever Gin has therefore nothing to do with the city of Geneva, but is simply Dutch Gin, also called Hollands or Schnapps, which at one time had a much larger sale in this country than the home-produced variety. In course of time, however, London established itself as the home of Gin, and London Gin (i.e. that actually produced here, not spurious versions made overseas) has for long been recognised as the finest in the world.

Formerly, the basis of Gin was invariably maize and barley, but since the beginning of the last war molasses have been increasingly used for the purpose. After distillation, the spirit is rectified (i.e. further refined) to eliminate impurities and produce virtually neutral alcohol. This pure spirit is then distilled with juniper berries, coriander seed, and various aromatic herb selected by – and secret to – each distiller. It is from the long-recognised medicinal properties of juniper that Gin gets its reputation of being “what the doctor ordered” (as he sometimes, apparently, does). Everything that comes from the still is not accepted: constant supervision is exercised, and that part of the “run” that does not come up to the required standard is sent back for further rectification. The number and sequences of distillation account largely for the differences in quality and cost of various Gins.

Age is no virtue where Gin is concerned, and maturing in cask does nothing to enhance its quality, and certainly not its purity. Gin is at its best, in fact, when it is straight from the still.

Those who enjoy Gin today as a congenial, subtly flavoured and beneficial form of spirit will rightly feel that its squalid past can now be, if not forgotten, at least forgiven. And indeed, it has not been the most insignificant of our age’s achievements to have driven the “demon” out of Gin and turned it into a civilised and discreetly used addition to the contents of the sideboard.

We are currently offering 15 percent off our award-winning No.3 London Dry Gin, as part of our Summer Sale.