From the ground up: why sustainable farming matters

Author: Sophie Thorpe

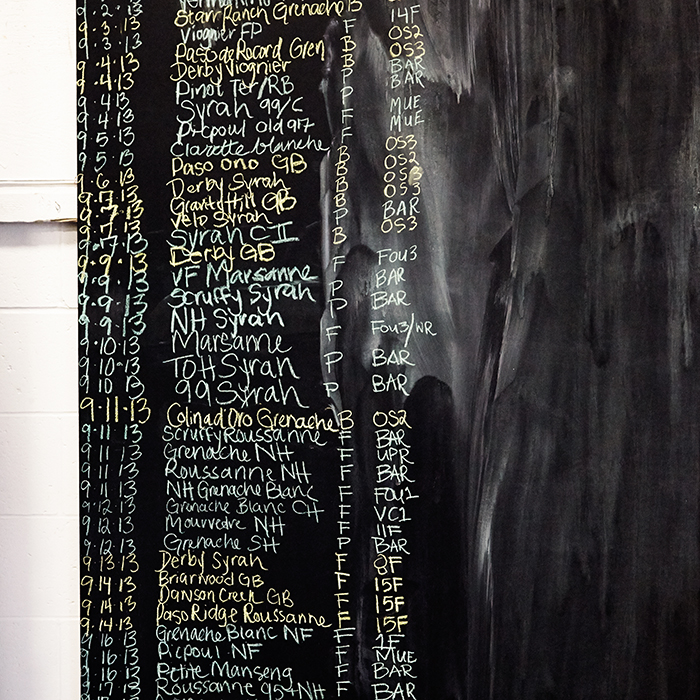

Work in the winery at Tablas Creek, Paso Robles, California. Photograph: Jason Lowe

“I’ve read Steiner backwards and forwards, and it made a little more sense to me backwards,” the jest-ful John Williams, founder and winemaker of Napa’s Frog’s Leap says – talking about Rudolf Steiner, the godfather of biodynamics. “I remain a little mystified by some of this…” Don’t we all.

Today the wine trade talks about organic, biodynamic, sustainable and – the most nebulous term of them all – natural wine, but what does it all really mean? We gathered three of California’s finest producers – the aforementioned John Williams, Jason Haas (General Manager and the American half of Tablas Creek – a partnership with Château de Beaucastel) and David DeSante (who with his wife Katherine, runs DeSante) in a room to dig beneath the compost, cover crops and cow horns to discuss just that.

***

Despite its famed hippy culture, California is looking to Europe when it comes to doing organic well – on home soil, it has something of a reputational issue to deal with. “California’s late to the game,” Jason says. “If you look at the percentage of vineyards that are certified organic in California, it’s well below any of the major European wine-producing countries.” This is, he says, thanks to a peculiarity of US regulations which means organic producers are unable to add sulphites during the winemaking process. “It has meant that a lot of the wines that were made with the organic seal in the early days were oxidised, or volatile,” explains Jason. “I feel like the US wine market is just finally recovering from that.” These negative connotations are just one reason that Tablas Creek has never used the organic seal on their labels. Jason worries about “the risk of being consigned to the ‘organic’ section rather than the ‘great wine’ section [of a shop].”

It is here that the unregulated realm of “natural” winemaking poses a threat. While wholeheartedly supporting the premise of natural wine, wine producers need to know that, as John Williams points out, it’s a risky path. “If you’re going to make wines in a more natural way, you really have to redouble your efforts to learn your craft.” All too many, he feels, are abandoning the “craft” to produce these wines, and that is having a negative impact on the whole category. “To some extent, it has meant that people think natural wine tastes like flawed wine,” Jason says. “There is, as there is with any movement, a tendency toward absolutism – it’s not truly natural unless you crush your grapes and walk away.” And that, as romantic as it might sound, is no way to make wine that expresses anything more than wine faults – mousiness, volatile acidity, brettanomyces (a yeast that can make wine smell “horsey” or “barnyard”) and more.

“We sometimes get caught up in all these terms, I think,” John says, “but in general what we’re talking about is inviting life, energy, living energy back into the farming system.” It might sound a bit touchy-feely, a little too un-British, but as David states “the soil is the most valuable resource we have.”

Green credentials aside, what better business reason could there be for paying attention? After all, if you don’t take care of the soil, your vines won’t flourish. John explains: “People attach organic to a wide variety of thoughts that aren’t necessarily part of what is organics. Organics is basically a soil-based fertility method.” He says it “brings a biological balance back into the soil, and out of this you return health to the farming system. And healthy living soil produces a healthy living plant which naturally resists disease.”

Industrial approaches to farming – particularly in California, home to big brands such as Gallo, Woodbridge and Sutter Home – can lead to an almost automated response to the land. As Chris Brockway (of Broc Cellars) says, some people “just spray chemicals ‘cos… it’s March 15th”. David emphasises that organics – or sustainable farming as an umbrella term – is “an awareness of not just rote-method farming, but really responding to situations as they arise”.

Cartoon: Jonathan Pugh, whose work appears each day in The Daily Mail

Tablas Creek has been organic since its inception, certified as of 2002, and turned down the biodynamic path in 2010, testing the methods on a 20-acre plot, which convinced them to farm the whole estate in that way, receiving certification last year. “Biodynamics was a very natural next step for us. We felt it would give us a better chance of keeping our vines healthy longer, maybe we wouldn’t have to replant the vines in 30 or 35 years, maybe we’d get 40 or 45 years out of them,” Jason told us. He was keen to use more of their own resources – for example, using compost from the sheep that munched on the cover crops between the vines, rather than bringing something in from beyond their estate.

It was tasting the wines from their test plot that persuaded Tablas Creek of the mysterious power of biodynamics. Ahead of blending each year, they taste each lot of each grape separately, blind (to remove any preconceptions). “That first year in 2010, all of the lots from the biodynamic blocks came out towards the top of the rankings. We thought that that was interesting but didn’t pay too much attention to it. The same thing happened the next year – and that was convincing enough for us. It wasn’t that they all tasted a certain way, they just had enough vibrancy and character that we picked them out blind,” Jason explained.

Like many producers, Jason isn’t necessarily converted to every aspect of biodynamics, and by his own admission, “I wouldn’t say that we take all the pieces of the biodynamic cannon equally seriously. In fact, there are pieces of it that we don’t pay much attention to – the calendaring, cycles of the moon…” – yet the proof is undeniably in the vinous pudding.

While Jason is encouraged that “a lot of people have been trying to move beyond the definitions of organic”, John worries that certification might offer too firm a goal. “If you stop and say I’ve reached this level of certification, therefore I am sustainable – that is dangerous thinking. We just need to keep peeling this onion.”

John urges that we all need to more – and that sustainability doesn’t stop with sulphur, sprays and soil health: “Where does your power come from? What kind of buildings do you build? What about your water sheds? These have got to become part of this discourse.”

The irony is talking about these farming methods being at the cutting-edge. Katherine DeSante put it eloquently: “Organic and biodynamic farming is exactly the opposite of innovation. It’s turning away from some of the farming innovations and going back and relearning what makes a healthy vineyard, what makes a healthy community. The grapes should be great, but more importantly the vines should be healthy, and the fruit trees around it should be healthy and the kids that are pulling the peaches off the peach trees shouldn’t need to worry about spray re-entry regimens. A lot of it is about going back to the way things were.” It’s a holistic view, one that might seem ever so slightly folksy and romantic, but easily encompasses every element of a wholesome approach to sustainability.

Unfortunately, there are no promises of quality just because a wine carries an organic or biodynamic label. “None of these are a guarantee of great wine. It just makes it somewhat more likely that you have a vineyard that’s healthy, or more resilient in the face of certain pressures,” says Jason. While many of my favourite producers operate within these philosophies, there are plenty who fit in the category whose wines I don’t rate. I care most for the talented producers who spend time in the vineyard and winery, making efforts to reflect a time and place with every bottle they make. Most importantly, I care about wine being delicious – but it’s interesting that, more often than not, that aligns with a sustainable approach.

Tablas Creek. Photograph: Jason Lowe

Progress is undeniably being made. John Williams held Napa’s first organic farming conference in 1989 and nine people showed up (“and I paid seven of them to be there,” he jokes); today the conference limits attendance to 200 people. David DeSante says that in his 25 years he has seen cover crops go from rare to commonplace.

There are plenty of unknowns ahead, though, as climate change hovers threateningly. Last year saw dramatic wildfires in Napa make headlines and right now California’s largest ever wildfire is raging through Coluso, Lake and Mendocino counties. “I think 2017 will be regarded as the vintage when the discussion changed. All of a sudden, climate change became a subject and what we used to consider was a slow-moving human crisis is now a fast-moving human crisis,” John says.

At the end of the day, it can seem precious to worry about whether there’ll be any Cabernet for us to enjoy with our dinner, but that isn’t really what this discussion is about. Ultimately winemakers are farmers, custodians of the land, and it’s high time we spent more time caring about what they’re doing to give us a good drink.

Learning the language of green

The requirements in the vineyard and winery vary according to region and – if certified – the certification body, but here is a general guide to what the key terms mean.

Organic: the focus here is mainly in the vineyard, improving soil health and avoiding man-made/industrial elements – using compost rather than fertilizer, not using fungicides or herbicides. Producers can use sulphur and copper-based sprays, as well as a few other select products.

Biodynamic: a step up from organics, this is the school of Rudolf Steiner (who also is behind the eponymous education system). The key principal is that a vineyard should be its own self-regulating ecosystem. Producers have to treat vineyards with biodynamic “preparations” at key points in the year, and farming is done in accordance with the biodynamic calendar, which reflects the lunar cycle.

Sustainable: not strictly regulated, sustainable practices aim to reduce the impact of today’s actions on the farmers of tomorrow – by, for example, having a responsible approach to water and electricity usage, protecting biodiversity, as well as having a long-term view when it comes to vineyard and soil health.

Natural: terribly fashionable, “natural” is a diaphanous term that isn’t legally defined, and can be bandied around at will. Those using the term are often – but not always – producers operating on the fringe of what’s possible, making wine with minimal intervention – think minimal technology in the vineyard and winery, native yeasts for ferments, neutral oak and little-to-no sulphur.

The taste of sustainability

2014 DeSante, Old Vines White, Napa Valley: From a remarkable dry-farmed old vineyard, this – believe it or not – comes from the younger section, planted in 1919 and the 1940s. An extraordinary field blend which includes the likes of Sauvignon Blanc and Vert, Tocai Friulano, Green Hungarian, Golden Chasselas and Sémillon, this rich and complex white offers notes of apricot, lemon pith, citrus, nuts and toast with a layered palate that has a slight savoury edge and a long, concentrated finish.

2015 Tablas Creek, Patelin de Tablas, Paso Robles: This is a more entry-level offering from Tablas Creek – but don’t let you put it off, all that means is that this is a juicy, bright wine drinking superbly now. A Rhône-style blend (based in Syrah), it is full of bright red and black fruit with a slight sweetness and spice on the nose. Fresh acidity balances its soft structure.

2016 Frog’s Leap, Zinfandel, Napa Valley: In John Williams’ words this is “barely legal” Zinfandel – co-fermented as it is with Petite Sirah and Carignan, both picked on same day. This blend helps reduce the sugar level, adding acidity and colour to the wine, and bringing it down to a deliciously drinkable, juicy and balanced 13.8 percent alcohol. It’s Zinfandel without the stomach-punch – with notes of rich strawberry, plummy, sweet fruit.

Thank you Sophie – an excellent article. We need more press like this for our organic wine industry. In South Africa it’s a real struggle.