From the archives: Raymond Chandler

Author: Berry Bros. & Rudd

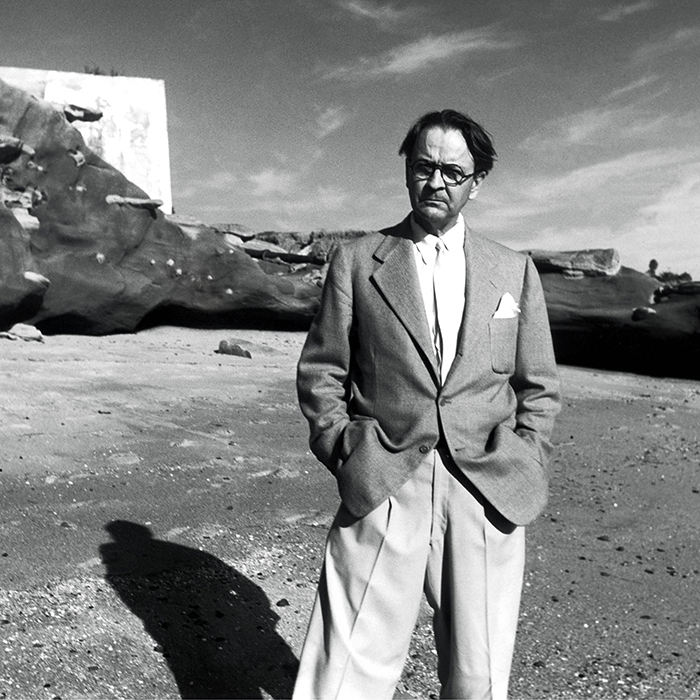

Raymond Chandler on the beach, shot for Vogue in 1947; photograph by George Platt Lynes, Condé Nast via Getty Images

Those of our readers who are familiar with the novels of Raymond Chandler may find it surprising that the creator of Philip Marlowe, that classic, hard-boiled American dick, was a patron of Number Three. On the face of it, the corrupt, brash world of California in the 1930s, represented in Chandler’s crackling prose, and that of St. James’s Street lie oceans and cultures apart. But the traditions and continuity of an establishment such as ours were qualities highly prized by the American writer, who, following the divorce of his parents, was brought up in England and educated at Dulwich College. The influence of his school and the classical education he received there had a profound effect on Chandler, who many years later was to cast his archetypal hero in a mould well-known to generations of English public schoolboys. Marlowe, who walks “down these mean streets” ostensibly carrying out his relatively lowly occupation, is a man of honour in an evil world. He is incorruptible, stoical, chivalrous towards women and the oppressed, relentless in his pursuit of truth and justice, indifferent to the vulgar lure of money.

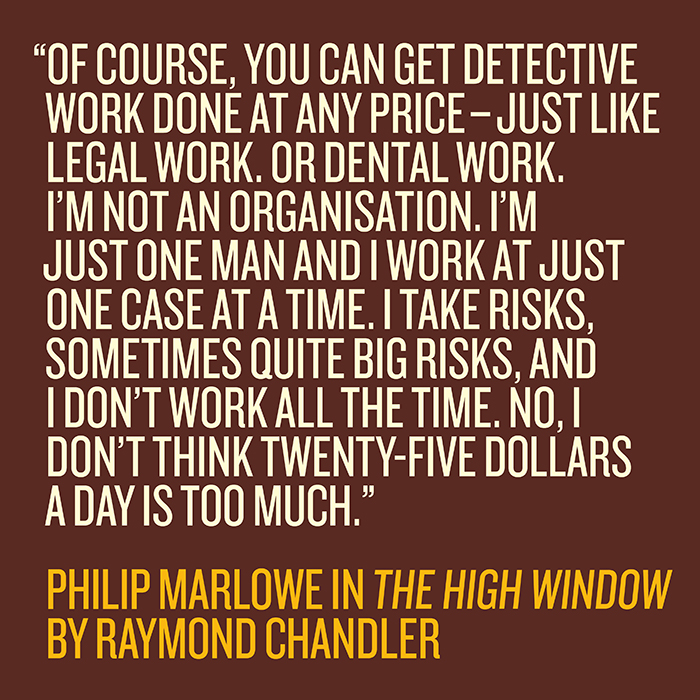

The zest and wit of Chandler’s dialogue, the craftsmanship of his narrative, succeed in bringing hero and setting authentically alive, particularly in the five full-length novels, beginning with The Big Sleep and concluding with The Long Goodbye, that established his reputation and earned him the admiration of the English intelligentsia. Unlike many authors, he really enjoyed writing and found constant entertainment in the richness of the American vernacular. Frank MacShane, his biographer, said that when he was living in California in 1961, he was told, “If you want to know what California is like, read Raymond Chandler”. A sardonic, sentimental and solitary personality, Chandler put a lot of himself into the character of Philip Marlowe, notably the isolation of a man who was never entirely at home in his own country. Marlowe’s life-style is ascetic: his marriage has ended on a sour note, his home is a place where he goes to sleep – alone; his office is functional to the point of bleakness; and his only indulgence apart from sexual skirmishes appears to be an occasional pint of good-quality Scotch.

Mr. MacShane, whose biography of Raymond Chandler was published two years ago by Jonathan Cape, quotes him poking fun at this suggested likeness to the characters in his books. “I am very tough and have been known to break a Vienna roll with my bare hands. I am very handsome, have a powerful physique, and I change my shirt regularly every Monday morning. When resting between assignments I live in a French Provincial château on Mulholland Drive. It is a fairly small place of forty-eight rooms and fifty-nine baths. I dine off gold plate and prefer to be waited on by naked dancing girls. But of course there are times when I have to grow a beard and hole up in a Main Street flophouse, and there are other times when I am… entertained in the drunk tank in the city jail… I am thirty-eight years old and have been for the last 20 years.”

Raymond Thornton Chandler was born in Chicago in 1888. His mother Florence was Irish and his father came from Philadelphia. The couple were divorced when their son was seven, and he accompanied Florence to England, where she shared with her mother and unmarried sister a house provided by Raymond’s solicitor uncle, Ernest Thornton. Young Chandler never heard of his father again: he grew up the only male in the household, bitterly resenting the dependent position in which his mother had been placed. While he was at Dulwich, he proved to be a clever boy with an aptitude for classics, but there was no money to see him through university. Instead, he was sent for a year to Paris and Germany to prepare for entrance into the civil service, and afterwards sat for examinations held for openings in the Supply and Accounting Departments of the Admiralty. Out of 600 candidates he was placed third, coming first in classics. But his ambition was to be a writer; he loathed the civil service and after six months he outraged his family by handing in his notice.

Finding it impossible to make a living by his pen in England, he borrowed £500 from Uncle Ernest and sailed for America. It was 1912, he was 23, and on board the steamer bound for New York he met the Lloyd family – artistic, intellectual, with connections in the oil business. Warren Lloyd and his wife Alma became key figures in Chandler’s life. To be near them, he settled in Los Angeles, where his mother joined him around 1916. The Lloyds found him jobs, provided the kind of social background he appreciated, and introduced him to his future wife.

Cissy was married to concert pianist Julian Pascal. She was 18 years older than Raymond Chandler, and Julian was her second husband. Chic, sophisticated and rather theatrical, she was still a beauty at the time they met, but it was only following Chandler’s return from service with the Canadian army and afterwards with the Royal Air Force during the Great War that their friendship developed. The calm of the Lloyd circle was ruffled, but everyone rallied to discuss the situation dispassionately, and it was in this civilised atmosphere that Julian Pascal agreed to a divorce. Florence Chandler refused to be won over: she disapproved because Cissy was so much older than her son, and it was four years later, after his mother died in 1924, that Chandler’s wedding took place. Raymond was 35 to Cissy’s 53. By this time, thanks to the influence of the Lloyds, he was working for an oil company where he had risen to be first auditor and shortly afterwards vice-president at a salary of $1,000 a month. At first, all went well with the marriage, but perhaps because of the age difference, Chandler began to go out socially on his own and to drink heavily. In 1932, at the age of 44, his behaviour had become so erratic that the oil company dismissed him.

Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in The Big Sleep (1946)

The blow sobered Chandler almost immediately, and with his wife’s encouragement, he turned back to his original preoccupation – writing. The need to be paid for what he wrote was now very urgent, and he deliberately set out to master the pulp magazine market, learning his craft slowly and painstakingly. Inspired by Dashiell Hammett and Erle Stanley Gardner, he took five months to write his first story, Blackmailers Don’t Shoot, which was accepted by the magazine Black Mask. A perfectionist in his style, he felt that detective fiction was a literary medium in its own right that he could use to express all the things he now had to say.

Chandler had travelled a long way since he was a print-struck boy of 23 seeking to make his fortune in America. He had seen and experienced much, but the pattern of his life – with and without Cissy – had been restless and rootless, moving to different houses and places in an uneasy quest for the ideal. This drifting, questing quality against a vivid Californian background comes over in his novels, the first of which was The Big Sleep, published in America by Alfred A. Knopf and in the UK by Hamish Hamilton – both old customers and good friends of the Berry family. Eventually, Chandler began to sell film rights of his novels, and became sought-after as a Hollywood script-writer, collaborating first with Billy Wilder on the film Double Indemnity for $750 a week. The strain and frustration of working for the studios set Chandler off on drinking bouts again, after many years’ abstention. “In Hollywood,” he wrote, “they destroy the link between the writer and his subconscious. After that what he does is merely performance. His heart is somewhere else.”

Although Chandler was a life-long Anglophile, it was 1952 before he and Cissy visited London, where the American mystery writer was much lionised by the critics. In 1955, broken up by the death of his wife the previous year, he returned alone. From then until his death in 1959, Chandler expressed a constant home-sickness for England, and returned several times. Frank MacShane reports his delight when the Daily Express ran a public opinion poll to establish the most popular authors, artists and entertainers in highbrow, middlebrow and lowbrow taste categories. Wrote Chandler: “Marilyn Monroe and I were the only ones who made all three brows.” Although he was invited out everywhere and made many influential friends in London, Chandler’s grief and chronic loneliness made him turn all too frequently to drink, which began to be a serious problem. In his book, Mr. MacShane records a tranquil hiatus in the troubled life of Raymond Chandler, English gentleman manqué. “His life during the summer of 1958 was quietly social and moderately sober. He liked to take a hired car on shopping expeditions to Harrods for clothes or gifts or to Berry Bros. & Rudd for whiskey and wines, and he enjoyed being driven to Boodle’s, the Athenaeum, or the Garrick for lunch…”