They came to Number Three: Evelyn Waugh

Author: Berry Bros. & Rudd

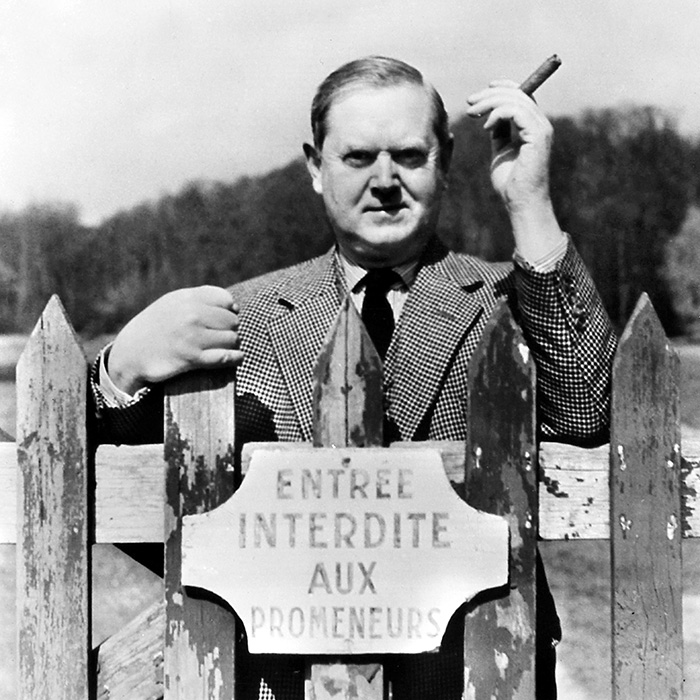

Evelyn Waugh, photographed in 1940

For a man whose life revolved around wine, Evelyn Waugh wrote surprisingly little on the subject. Even his novels have few references to this lifelong passion, although there is a famous passage from Brideshead Revisited, when Charles Ryder, staying with his friend Sebastian, “first made a serious acquaintance with wine and sowed the seed of that rich harvest which was to be my stay in many barren years”. Many will remember the scene when they sit up late in the Painted Parlour, getting their glasses more and more muddled as their praise for the wine grows wilder and more exotic:

Goodness knows how many sottish late-night conversations that passage has inspired among later generations of Oxford undergraduates, but I feel it belongs among the immortal pieces of wine writing, along with Thurber’s famous caption, from Men, Women and Dogs: “It’s a Naïve Domestic Burgundy, Without Any Breeding, But I think You’ll be Amused by its Presumption.”

One might also deduce from the scarcity of Evelyn Waugh’s writing about wine that it belonged to that part of his life which he regarded as private. The fierceness with which he defended his own privacy gave rise to many of the stories – gossip columns were full of them – which portrayed him as a monstrous old blimp, roaring and yelling at any intruder into his private domain. In fact he was a gentle, humorous man – sometimes sad, sometimes gloomy – and nowhere near as bad-tempered as he appeared to the Press and public on his few excursions outside the small world of family and friends. But I do not think it is betraying a trust to reveal an aspect of his private life which will be of great interest to wine-drinkers and which has never, so far as I know, been revealed before.

The mid-life crisis is familiar among males in our society. Many mark it by leaving their wives of many years and taking up with some luscious young dolly bird or, if they are not married (like Bernard Levin) they may give up their work and go to live at an ashram in Poona. Evelyn Waugh celebrated his own mid-life crisis first of all by going mad soon after his 50th birthday, in January 1954. This episode is well documented in his novel, The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold, first published in 1957 but available in Penguin. Next, having recovered his sanity, he sold his house and moved to the huge icebox at Combe Florey, in Somerset, where I now live. In the process, he suffered a violent change in his wine-drinking habits which was to remain with him for the rest of his life – he died in 1966 – as the only permanent trauma from his experiences at this time. From that moment, he could never touch a drop of claret, under any circumstances.

It would be interesting to know if others have had the same experience in middle age. His house in Gloucestershire was famous for the excellence of its clarets – as for its vintage ports – but just before moving house, in the late autumn of 1956, he sold every bottle of claret in his cellar, and never bought another. Worse than this, he could not bring himself to drink any red wine from Bordeaux even in the house of friends. A year ago I found myself sitting next to Sir Hugh Greene, the former Director General of the BBC. Like the Ancient Mariner, he held me with his skinny hand and told me a tale of woe which had understandably been haunting him for years. It appeared that at some time in the early 1960s, probably 1963, Evelyn Waugh had visited the BBC to make a broadcast about P.G. Wodehouse, and Greene had decided to give a dinner party at Broadcasting House. In Waugh’s honour, Greene had procured rather a special bottle of claret – not just rather a special bottle, but the classic, never-to-be-forgotten Cheval Blanc 1947. Evelyn Waugh thanked him very much, but declined to take any. End of story.

Plainly, this violent repudiation of the world’s second best wine-producing area was the result of some psychological trauma, if not actual brain damage. He was quite happy to experiment with wines from unlikely places like Chile (probably of Cabernet base, although in those days they did not specify the grape) and once discovered a new enthusiasm for the red wines of Germany. Even more shaming than that, he came back from Rhodesia one day announcing a new discovery from Portugal called Mateus Rosé, and drank it through one whole summer. Whenever challenged with this, I loyally maintain that the Mateus Rosé of the late ‘50s was a quite different wine from the sugary pink fizz of today, but I do not honestly know where the truth lies.

Evelyn Waugh, photographed by Cecil Beaton at Ch. St Firmin, Chantilly, France, 1955.

At any rate, no claret ever entered the cellar at Combe Florey until 1971, when I moved back. At Evelyn Waugh’s death in 1966 he left four or five dozen Chambertin 1955 from Berry Bros – a magnificent wine, but one which would have improved with keeping in less frigid surroundings than the cellars at Combe Florey. Although, so far as I know, no wine has ever actually frozen solid down there, I cannot think why not as the temperature in his day was frequently below freezing point. He also had two cases of Richebourg from Berrys’ – I think the vintage was also 1955 – some odd parcels of rather old Sauternes, notably Suduiraut 1947, and a lot of champagne, notably Clicquot Rosé for which he had developed an old man’s passion. There were no bottles of vintage port and nothing else.

I think I may have one clue, which is neither psychological nor biochemical, for Evelyn Waugh’s repudiation of claret. For some reason, he always referred to it as “clart”, even in such homely expressions as “to tap the claret”, meaning to draw blood in a fight. “Have a glass of clart,” he would say. Some had difficulty in understanding what he meant, but he persisted. Then in 1956 there was published a rather shameful book called “Noblesse Oblige”, edited by Nancy Mitford, with contributions from herself, Waugh, John Betjeman, Christopher Sykes and others discussing the characteristics of the English upper class. In the course of his contribution, Sykes – who was a friend of my Father’s despite being, as he frequently pointed out, of better breeding – mentioned “a Gloucestershire landowner” who believed “that persons of family always refer to the wines of Bordeaux as ‘clart’, to rhyme with cart”. Mr Sykes opined that “this delusion” showed “an impulse towards gentility” which might be preferable to the contrary impulse, among true aristocrats, towards affecting the mannerisms of the proletariat.

My Father spotted the reference to himself immediately, and although he took it in good part, it must have left him in something of a quandary. Either he had to drop his harmless affectation in deference to the mockery of a younger man and lesser artist, which he did not deign to do, or he had to persist in the awareness that everyone was sniggering at him as the Gloucestershire landowner who said “clart” when he meant “claret”. I do not know how much influence it had on his subsequent behaviour, but it is fact that within a year he had sold not only his house in Gloucestershire but also all his claret, and never touched the stuff again.

I cannot leave the subject without touching on Evelyn Waugh’s wine-writing such as it was. His main contribution to the field ( I exclude his work on a history of Veuve Clicquot) was a booklet called Wine in Peace and War published by Saccone and Speed in 1947. It has never been reprinted, and has little of contemporary relevance in it. I observe from his correspondence with his Agent, A. D. Peters, that he was paid at the rate of 12 bottles of champagne per 1000 words – not an immensely generous rate, I would say. Perhaps that explains why he wrote so little on the subject. I am sure he could have done better.

The last thing he wrote about wine appeared in the New York Vogue in the year before he died. It dealt with champagne, and described the circumstances in which it should be drunk: “For two intimates, lovers or comrades, to spend a quiet evening with a magnum, drinking no apéritif before, nothing but a glass of cognac after – that is the ideal… The worst time is that dictated by convention, in a crowd, in the early afternoon, at a wedding reception.”

That comment strikes me as profoundly true. Immense harm is done to champagne by the English habit of drinking it, usually warm and in a sort of trifle dish, at weddings in the early afternoon. That is why so many people in England claim to dislike champagne.

An even profounder claim is made in the first writing I have been able to trace by him in the December 1937 issue of Harper’s Bazaar, under the title “Laying Down a Wine Cellar”.

“Wine lives and dies; it has not only its hot youth, strong maturity and weary dotage, but also its seasonal changes, its mysterious, almost mystical, link with its parent vine, so that when the sap is running in the wood on the middle slopes of the Côte d’Or, in a thousand cellars a thousand miles away the wine in its bottle quickens and responds.”

I wonder if there is any truth in this theory. We have all noticed extraordinary variations from bottle to bottle within a matter of a month or two but I have never thought of relating them to seasonal changes in Burgundy, Bordeaux, the Lebanon or wherever. Perhaps it is true that many wines – not ports nor old-fashioned “cooked” Burgundies – go to sleep in the winter. If this is true, we should drink Australian, South African and Chilean wine throughout the winter, French wine only in the spring and summer months. Californian wines, by the same token, can be drunk all the year round.

Or perhaps it is all a load of codswallop. I was never entirely convinced that my Father, for all his poetic gifts, knew very much about wine. Certainly his brother, Alec, knew much more. When Evelyn wrote those words, he was just laying down his first cellar. My Grandfather, Arthur Waugh, who was a publisher and critic, drank nothing but Keystone Australian Burgundy, a beverage which he believed to have tonic properties, much to the embarrassment of his two sons.

Even so, my Father, who wrote in 1937 that “nothing is easier than to ruin a fine wine by careless handling”, was among the worst offenders in this respect. He never brought up a wine to the dining room much more than half an hour before a meal – not that it would have made much difference if he had, as the dining room was nearly as cold as the cellar; and he never opened a bottle before it was time to drink it. In his last years he drank splendid Burgundy, day after day, at temperatures which many would judge too cold for Sauternes.

But the saddest part of the article, written as a young man of 33, concerns ports of a great vintage; it is at least 15 years before they become drinkable, and 50 before they are at their prime; some superlative vintages will live a century. It is these vintages which one should buy as soon as they are shipped and lay securely down for one’s old age, or for posterity.”

Perhaps he had rather lost his enthusiasm for posterity by the time he died, at the sadly young age of 62. Despite his golden opportunity to lay down the 1963 vintage before his death in 1966, he left no port at all.

[…] wine merchants Berry Bros & Rudd have posted on their internet site an article by Auberon Waugh about his father’s knowledge of wine. This originally appeared […]