More than just a name, ‘Valpolicella’/‘Valle delle tante cantine’/‘Valleys of many wineries’…

Author: David Berry Green

I returned to Valpolicella in trepidation as to what I might find, and eat. The promising news is that there appears to be a wave of younger Venetians willing to forsake easy sales of fruit to the local Cantine Sociale (originally set to gather votes as well as fruit!) and give (fine) winemaking a go; that and a key improvement in the cucina! The (wine producing) field remains split, as per the regions* between those emulating the traditional ‘Classico’ Quintarelli model (unirrigated, minimal intervention, long appassimento and invecchiamento, pale coloured mineral wines) and those aping the modern ‘non-Classico’ Dal Forno path (irrigated, max intervention, short this and that, giving dark fruited impact wines). The former requires prime terroir; the latter not.

I returned to Valpolicella in trepidation as to what I might find, and eat. The promising news is that there appears to be a wave of younger Venetians willing to forsake easy sales of fruit to the local Cantine Sociale (originally set to gather votes as well as fruit!) and give (fine) winemaking a go; that and a key improvement in the cucina! The (wine producing) field remains split, as per the regions* between those emulating the traditional ‘Classico’ Quintarelli model (unirrigated, minimal intervention, long appassimento and invecchiamento, pale coloured mineral wines) and those aping the modern ‘non-Classico’ Dal Forno path (irrigated, max intervention, short this and that, giving dark fruited impact wines). The former requires prime terroir; the latter not.

Of the fifteen cantine visited over four-and-a-half days – cantine selected for their artisan size/focus – 40% reflected the more extracted style as championed by Dal Forno, the rest finding solace in the soil. But then as Paolo Galli of Le Ragose stated, admittedly from his historical vantage point above Negrar, ‘you can’t buy experience’; nor prime sites unless you’re willing to rebuild abandoned terraces – one I met had spent four years piecing together a two hectare vineyard. Faced with such ‘adversity’ and an increasingly competitive market, ‘new-start’ cantine are taking refuge in the technology to see them through rather than trusting in the trowel.

– 40% reflected the more extracted style as championed by Dal Forno, the rest finding solace in the soil. But then as Paolo Galli of Le Ragose stated, admittedly from his historical vantage point above Negrar, ‘you can’t buy experience’; nor prime sites unless you’re willing to rebuild abandoned terraces – one I met had spent four years piecing together a two hectare vineyard. Faced with such ‘adversity’ and an increasingly competitive market, ‘new-start’ cantine are taking refuge in the technology to see them through rather than trusting in the trowel.

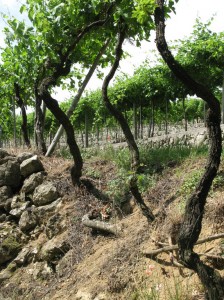

In these warmer times it seems that the pergola trellising system may be making a comeback, with its higher acidities, even if the higher density guyot produces a richer, earlier, more even crop year-in, year-out. The change in the weather has also accelerated a flight to the hills, in search of relief and terroir; Dal Forno for one has just bought a piece up from the valley floor in the valley of Mezzane di Sotto.

It was heartening to come across producers who had not chosen to ‘muddy the waters’ and manipulate the must (with rotos, cryomaceration, selected yeasts, enzymes, tannins etc…). I applaud the ‘traditionalists’ who seek to convey the quality of their ancient volcanic and calcareous terroir to shine through giving wines of real identity, distinction/nobilità, and drinkability. It’s a terroir particularly visible among the ‘Classico’ valleys of S.Ambrogio, S. Pietro in Cariano, Fumane, Marano (left), and Negrar, with fine sites at 250-350 metres, but also elsewhere, as per the high chalky site above Mezzane di Sotto, home to Marinella Camerani’s property Corte Sant’Alda (in the video below). It’s a terroir that deserves to be articulated clearly through the wines.

It was heartening to come across producers who had not chosen to ‘muddy the waters’ and manipulate the must (with rotos, cryomaceration, selected yeasts, enzymes, tannins etc…). I applaud the ‘traditionalists’ who seek to convey the quality of their ancient volcanic and calcareous terroir to shine through giving wines of real identity, distinction/nobilità, and drinkability. It’s a terroir particularly visible among the ‘Classico’ valleys of S.Ambrogio, S. Pietro in Cariano, Fumane, Marano (left), and Negrar, with fine sites at 250-350 metres, but also elsewhere, as per the high chalky site above Mezzane di Sotto, home to Marinella Camerani’s property Corte Sant’Alda (in the video below). It’s a terroir that deserves to be articulated clearly through the wines.

This is also the view of the Consorzio, as they look to ‘rediscover the lost identity’ of the region. Not only have they facilitated the DOCG for Amarone and Recioto, partly to reflect the quality but also as a measure of increased control (and lower yields), but moreover they have begun promoting the individual sub-zones; no doubt in time to become ‘crus’ as here in Piedmont.

*The total surface area of the Valpolicella district is approx. 30,000 hectares, of which hillsides (75%), valley floors (17%) and urban areas (8%). Of this 6,300 are vineyards (20% planted in the last 10 years), split equally between the historical ‘Classico’ area (fie communes above) and the more recent ‘non-Classico ’ (14 communes) extension. Interestingly of the ‘Classico’ region ‘hillsides’ represent 60%, while this figure is 46% for the ‘non-Classico’ zone. There are 2600 farms averaging 2.16 hecatre, with 93% of properties having fewer than 5 hectare – source il Consorzio per la Tutela dei Vini Valpolicella.

Thanks for this interesting post. Which of the more Classico/traditionalist producers do you think are making the most interesting wines?

Hi Gavin – thanks for your kind words but sorry, at this stage I’m afraid that’s ‘classified’ (information!) until such time as I’ve made my decision as to which cantine we team up with! That probably sounds pompous but isn’t; I just need some time to reflect! I’ll be revealing all over the coming weeks…. suffice to say Corte Sant’Alda, Quintarelli & Le Ragose are fine places to start!

I will also add to your list Amarone Bertani Classico. That used to be one of the most classical and elegant amarone. Unfortunately new barrels have been introduced by the end of the nineties that had chaned a bit the aromatic profile. But some bottles form the late sixties and mid-eighties are still absolutely incredible. 1995 was also one of my favorite.

Another classic style producer is Bussola, pay attention if TB is mantioned on the lable, in that case the wines have been matured in small oak barrels.

indeed, we’ve bought their Vigneto Alto TB & Recioto TB in the past…the estate has grown to quite a size, to fill the new cantina/palazzo no doubt…

DBG

Okay, fair enough. Thanks for the suggestions, and I’ll look forward to seeing which estates you end up teaming up with.