The Grocer of St James’s Street | Part 1

Author: Berry Bros. & Rudd

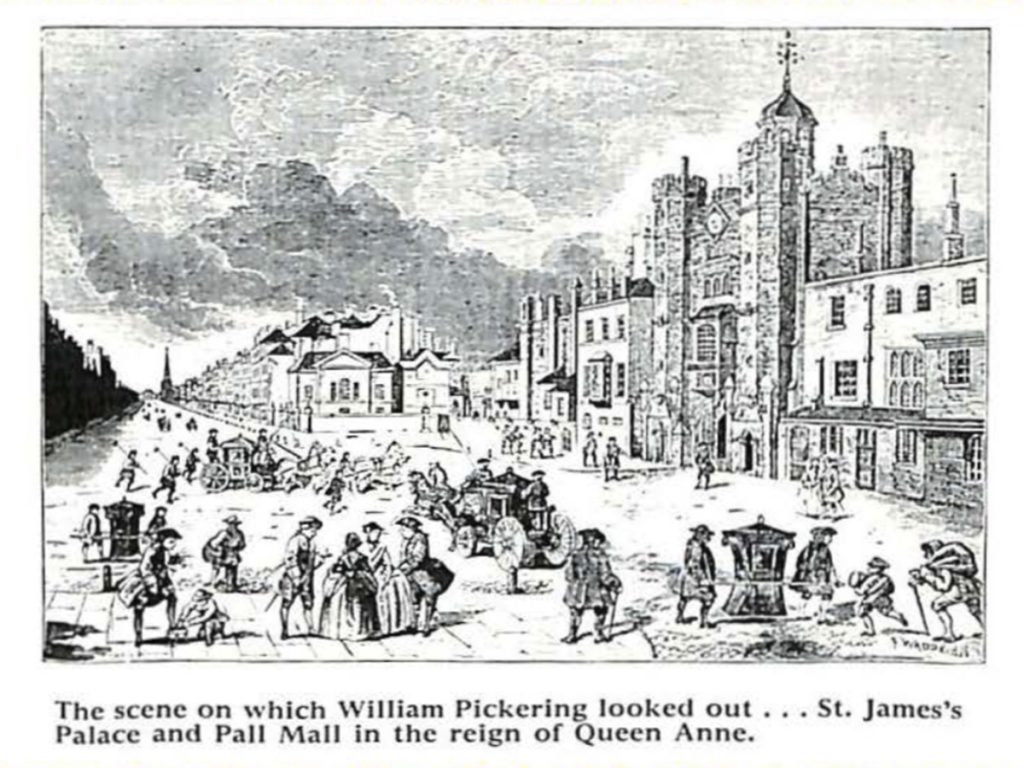

Some 300 years ago, William Pickering laid the foundations for our business. This article is the first of two parts, originally published in Spring 1958. It dives into 17th-century St James’s Street, opening the doors on the Heraldic Painters and Coffee Mill which paved the way for the wine and spirits shop to come.

Amongst the legion of ghosts that must surely drift over the gnarled floor of No.3, or linger dimly in the cellars, it is pleasant to think that the approving spirit of William Pickering, “The Grocer of St James’s Street”, returns at times to witness the continued prestige and prosperity of the business he did so much to further over two centuries ago.

When William Pickering came to No.3, he came not merely to buy but to enter the business as the virtual founder of our firm in its present form. A key figure in our history, his life draws together the threads of the 16th and 17th centuries and those of a later age to give us a glimpse of both our business and its environment in the making: the St James’s Fields of his ancestors’ day developing into the St James’s Street known to his descendants; Stroud’s Court reassembling as Pickering Place; and Bourne’s Italian Warehouse taking shape as Berry Bros. and Rudd wine merchants.

He was born in 1675 in Edenham, Lincolnshire, where his father Thomas Pickering was a tailor. Thomas died when his son was 17, leaving £5 each to William and his daughter Avis “when they shall attaine to the age of 21 years”. Two years later, the scene shifts to London, where we find that on 5th September 1694, William Pickering was bound apprentice for seven years to Zachary Hutchins, Painter Stainer or Heraldic Artist.

St James’s Street in Tudor times

Several Pickerings before him had belonged to this fraternity, which flourished in the colourful days of the Middle Ages, when its main source of income was the armorial painting of saddle-bows for tournaments. The Painter-Stainers also boomed during the time of Henry VIII, when the Field of the Cloth of Gold typified the vainglorious extravagance of the age.

Typical, too, was Henry VIII’s demolition of St James’s Hospital, originally endowed by the citizens of Norman London for the benefit of 14 leprous maidens. This had grown to a considerable establishment when Anne Boleyn, riding gaily through the green fields of St James’s with a hawk at her wrist, cast calculating eyes at the hospital, and suggested to her lover that it would be the ideal place for her to dwell, “where the eyes of Whitehall could not gaze on her”, and yet within easy reach.

Henry bundled off the leprous virgins to Chattisham in Suffolk, and built a “goodly manor house” in 1532 on the hospital site, which later became St James’s Palace. After Cranmer had declared Henry lawfully married to Anne, she did not live very long to enjoy her new royal residence; but the “ferme house” that stood opposite the Palace against the North Gate, and which had probably supplied the hospital with milk, butter and eggs, was no doubt a beneficiary of royal custom.

The transformation of St James’s Street

When young Will Pickering came riding up to London to try his fortune, however, the “ferme house” had vanished, and in its place was a block of buildings that had been built during the intervening years, as the district of St James’s gradually emerged from a lonely hamlet into a village, and finally, a new suburb. There is every reason to believe that the foundations of the farm house, and perhaps even some of the original timbers, were contained in those buildings, two houses of which occupied the site of No.3.

James I, that canny hypochondriac, issued proclamations in 1607 and 1609 forbidding the erection of buildings on new foundations in the City, or within two miles of it. This was partly because he foresaw the danger of overcrowded areas, and partly to keep the plague-ridden popular breath well clear of his shambling Majesty at Whitehall. There was therefore every incentive for building speculators to use old foundations such as those for the farm house.

According to the Rate Books of 1695, Thomas Stroud occupied one of the houses at No.3, and is the first known resident there; he also gave his name to the four houses of Stroud’s Court that he built, which was approached at that time by a narrow passage running between the two houses at No.3. By 1696, Thomas Stroud had left St James’s, and the new tenants at Stroud’s Court are listed in the Rate Books as “Lowls Burdoffo” and “Cuarios Caproolo” — obviously the rate collector’s stab at spelling Italian names. It is possible that “Burdoffo” was the founder of the Italian Warehouse or Grocery known as the Coffee Mill that was certainly in existence a few years later when the Widow Bourne began, or possibly took over, a business there in 1698.

By this time, Will Pickering was two years short of completing his apprenticeship. The Widow Bourne and her Coffee Mill must have become well known to him as he went about his business in St James’s Street – as must have been the bright gaze of the widow’s pretty daughter, Elizabeth. We have no means of guessing how long William’s courtship of Elizabeth was, especially as the Rate Books for 1703 and 1704 have been lost. But in 1705, the Rate Book lists “Will Piccaring” as paying £16s 8d in place of the Widow Bourne. William Pickering had arrived at No.3 at last. He had captured the widow’s daughter, her house and her business.

To be continued…