They came to Number Three: The Prizefighters

Author: Berry Bros. & Rudd

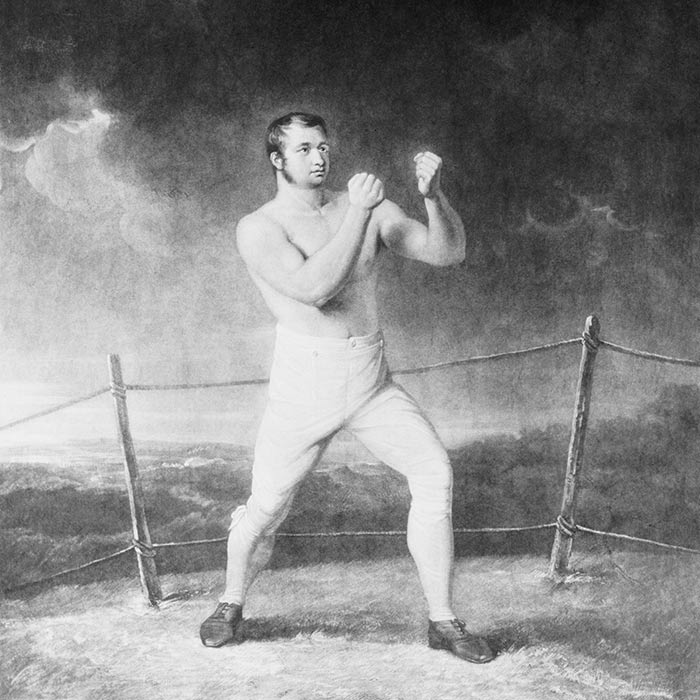

Tom Cribb, Champion of all-England. Bettmann/Getty Images

The Irish singer and poet, Tom Moore, and Lord Byron were keen followers of “the fancy”, so it is just possible that either of these habitués of Number Three arranged the weigh-in at our shop; but a more likely customer to have been responsible was a Captain Robert Barclay, Cribb’s patron and trainer. The occasion would have aroused tremendous interest among the young bloods, already debating which of the two heavyweights to stake on the appointed day when Belcher, the defeated champion, met Cribb for the second time in an attempt to regain his former supremacy. The Prince Regent and his brothers, the Royal Dukes, whose enthusiasm for prizefighting had done much to make it so popular with the sporting nobility, would not have been above questioning young George Berry closely about how the two pugilists shaped up on Number Three’s scales. And the wine merchant’s son, just turned twenty-one, would no doubt have been thrilled with his role as witness to such a stirring event at grandfather John Clarke’s premises, and blessed the day of opportunity five years previously when he had come up from quiet Exeter to work in fashionable St James’s Street.

One character in this little drama who would have taken a long, cool look at the evidence of our scales, probably noting that his man needed paring down by a stone were he to be successful in the return bout against the hard-muscled Jem Belcher, was Captain Robert Barclay Allardice of Ury, Kincardineshire. At that time Captain Barclay (as he was always known) was about 29 years old – two years senior to the boxers, who were much of an age. A noted amateur athlete accustomed to sparring with all the best bruisers of the day, Barclay was yet to accomplish his matchless feat of walking 1,000 miles in 1,000 successive hours, which he achieved in June and July of the following year. His training methods called for drastic reductions in weight, and it is interesting to see form our records that he applied them equally to himself. On April 20, 1812, he is shown as 10 stone 11 in boots; when he called again at Number Three five days later, he had shed five pounds. Bernard Darwin includes in one of his anthologies an account by an eye-witness of Tom Cribb’s last fight with the formidable black American, Tom Molineaux. “Barclay had Cribb in Yorkshire to train; he made him plough, and fill a dung-cart – all the hard work that ever he could put him to. He was in beautiful condition, fine as a star, just like snow aside a black man. The black man was fat – that licked him as much as anything.” But the main feature of Barclay’s system was to make his protégés walk immense distances daily at a terrific pace. Starting at 16 stone, Cribb lost more than one-sixth of this weight under his patron’s direction.

A former coal porter nicknamed at the start of his fighting career “The Black Diamond”, Cribb was 25 in 1807 when he was introduced to Captain Barclay, whose interest and patronage was considered the stepping stone to success for promising young pugilists. Barclay took his training in hand and thought so well of his form that he backed him for 200 guineas in April the following year against Jem Belcher, the reigning champion, who is regarded as one of the finest of all the old-time prizefighters. Boxing in those days was a brutal, slogging sport fought with bare knuckles in the open on a grassed area or wooden platform.

In 1743, Jack Broughton, traditionally accepted as the father of British pugilism and the inventor of the boxing-glove, introduced a set of rules that forbade antagonists to strike opponents when they were down, or to seize them anywhere below the waist. Otherwise, no holds were barred and wrestling played a big part in the battles of the bruisers. A round ended when a man fell, and only half a minute was allowed for him “to come up to scratch” – the centre of the ring – and begin a new round.

Fighting was in Belcher’s blood; he was a descendant of Slack of Norwich, a famous champion who succeeded Broughton, while his brother, Tom Belcher, was also highly regarded as a pugilist. When the two men met again at Number Three, it is likely that Belcher would have been in surly mood, taunting the upstart whom he had soon challenged again for the stakes of a belt and 200 guineas, and fully expected to beat. Tom Cribb, on the other hand, was a genial, kindly character, respected for keeping his temper whatever the provocation. He had a protruding bar of frontal bone above deep-set eyes; it was a feature that could hardly have rendered him handsome, but it gave him natural protection against one of the main strategies in bare-fisted English prizefighting, which was to make an adversary’s eyes swell up so that he could not see properly. At Epsom on February 1, 1809, to the astonishment of Belcher’s friends and backers, Cribb defeated him for good, and the former champion had to resign his belt. He died in 1811, aged 30.

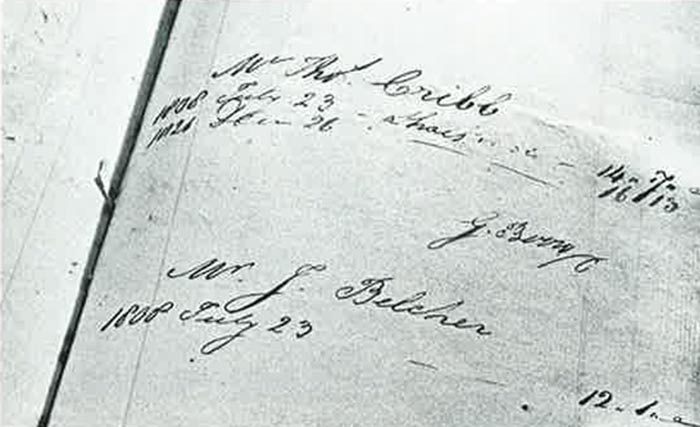

The prizefighters’ weights recorded in our books

The reputation of Cribb, meanwhile, had risen to even giddier heights following his defeat on December 18, 1810, of the formidable black American, Tom Molineaux. The international flavour of the fight, when the honour of England was at stake as well as that of Cribb the favourite, made it a matter of great excitement and interest. The whippers-out, drawn from the ranks of the prizefighters, were kept busy beating back the crowd with their long lashes, and there was many a nobleman’s carriage drawn up at vantage point to observe every move of the two heavyweights. Did George Berry, we wonder, now well in the saddle at Number Three with his own name above the door, take time off from his business to help cheer on the champion in whom he had so special an interest? At all events, “the buffs” were not denied their thrills, for the contest was touch and go for Tom Cribb. He went down before the powerful negro’s smashing blows in the 23rd round, and it looked as though there was no chance of his coming up to scratch in time. At this point Cribb’s second went up to Molineaux’s corner and accused the American of holding bullets in his hand; this was indignantly denied, nor did the champion’s second believe it himself, but the altercation gained precious extra seconds for his man’s recovery. Up cam Cribb, full of pluck, and went on to defeat Molineaux in the 33rd round.

It would have been the incident of the bullets that encouraged Molineaux to challenge Cribb again, for a second meeting was arranged on September 28, 1811 at Thistleton Gap, Leicestershire, before over 20,000 spectators – a fourth of whom were reckoned to be members of the aristocracy and upper classes. Cribb’s second was John Gully, a former prizefighter who fathered 24 children and eventually became MP for Pontefract; and the referee was “Gentleman” John Jackson. Jackson’s patron when he was active in the ring had been none other than the Prince Regent, and he earned over £1,000 a year teaching sparring at his famous Saloon in Bond Street.

To the great disappointment of the eager crowd, the fight only lasted 20 minutes. Molineaux’s jaw was fractured in the 9th round, and his backers had to throw in the sponge by the 11th round because the American could no longer stand. Cribb, to show he was as fresh as ever and to entertain the spectators, is said to have danced a hornpipe all round the ring with Gully. The fight earned £400 for the champion but his patron, Captain Barclay, was £10,000 richer through Cribb’s triumph.

Cribb never fought again in public, although in June 1814 he put on a sparring exhibition at Lord Lowther’s house in Pall Mall for the Russian Emperor, and again two days later for the King of Prussia. In 1820 he was one of 17 celebrated pugilists who, dressed as pages, were engaged to guard the entrance to Westminster Hall at the coronation of George IV. In 1821, it was decided that as Cribb had held the championship unchallenged for ten years, he should retain the title for the rest of his life.

By this time he was a near neighbour of George Berry as mine host of The King’s Arms, at the corner of Duke Street and King Street, St. James’s. The inner sanctum of this hostelry was known as Cribb’s Parlour, and only favoured customers, such as the aristocracy and celebrities of the prize-fighting world, were allowed over its threshold to fraternise with the landlord. It was said to be a favourite sport with young noblemen to try and take a poke at Tom Cribb for the prestige of saying afterwards that they had been knocked down by the champion, but the good-humoured landlord put a stop to it by refusing to retaliate and hauling them before a magistrate. In 1828, Cribb moved to the Union Arms, Panton Street, Haymarket, but he was no businessman like Gentleman Jackson or John Gully, and in 1839 he handed over the Union Arms to his creditors. Former comrades and admirers provided him with a comfortable annuity, however, and he died aged 67 at the house of his son, a baker and confectioner in High Street, Woolwich.

During the prizefighter’s reign at The King’s Arms, it is likely that George Berry, a key witness on that occasion at Number Three when he was a rising star in the boxing world, would have been one of the customers who was welcome in Cribb’s Parlour. The champion may even have consulted the young wine merchant about the drink he should supply for his aristocratic patrons. From our records, we know that Cribb returned at least once to Number Three; the entry date in our Weight Books is a little blurred, and could be December 26, 1821, or 1826, but it shows that easier living had taken its toll, for the champion – always inclined towards beefiness – at this time weighed 16 stone 13.