From the inside: dangerous descriptions

Author: Berry Bros. & Rudd

One of our many pleasant memories of evening spent with the Sainstbury Club* is of an occasion shortly after the war when Mr. Charles Morgan was the speaker and took the opportunity to reproach M. André Simon good-humouredly about the style of his writings on wine. “What you say of wines is so dangerously often applicable to ladies, ” he pointed out, “that it may cause confusion in the minds of our younger members.”

Mr. Morgan proceeded to quote chapter and verse in support of this charge, “changing,” as he explained, “nothing but a pronoun.” Here is one of his examples:

Somewhat short in the nose, she gave more than she promised – a good fault. Full of life: silky, serious, robust and elusive; refined and expanding; she left behind, as she departed, a sense of complete gratification without the least feeling of satiety.

“Really,” the speaker demanded of M. Simon to the great amusement of the company, “what are you describing? Château Ausone 1909 or Cleopatra?”

He went on to cite “a less romantic, indeed a wickedly cynical” passage:

When she was quite young, none could be more attractive, and yet with a little age, barely a dozen years in bottle, she faded to sugar and water and was worthless.

On which Mr. Morgan’s comment was: “We are all only too familiar with ladies of whom that is a precise description… You pretend that what you were writing about was a Cheval Blanc born in 1923, but you knew quite well that no one would believe you.”

Mr. Charles Morgan is not by any means the only to have called in question the literary integrity of wine connoisseurs. We imagine that Sir Norman Birkett, K.C., was expressing a not uncommon feeling when he confessed, in a “Memoir” contributed to the 1949 edition of the late Maurice Healy’s book Stay Me With Flagons, that the language of wine experts “occasionally seems to me to be a little forced and artificial, and if it is not plain blasphemy to say so, at times a trifle ridiculous.”

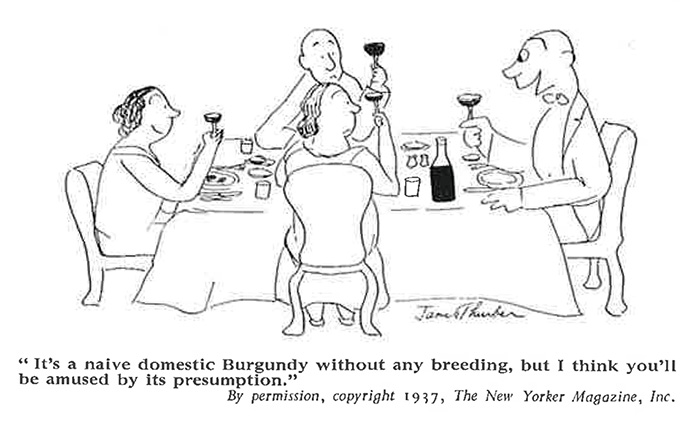

After referring to the Thurber cartoon which we reproduce below, he went on to quote from Maurice Healy’s own chapter on Burgundy the following description of what would clearly be fitting male company for M. Simon’s voluptuous ladies:

When one thinks of Bertrand du Guesclin the image is as much of good manners and courtesy as of valour; so I shall borrow him as a type of Romanée Conti, ranking the others as his brothers-in-arms. For the suavity of these wines would not show to such perfection were it not for their valour and sturdiness. They are indeed princely wines, and the qualities that lurk in their depths are courage and fair dealing.

There is no need of further illustration to show how easy it is to make fun of the pictaresque, and sometimes high-flown, style of much writing about wine. It has to be remembered, however, that someone who sets out to record his impressions of wine is attempting a notoriously difficult task. The equivalent would be to ask a gardener to describe the scent of one rose and compare it verbally with another.

So if the wine commentator sometimes resorts to strange similes and far-fetched images, his motive is not literary preciosity, still less snobbery, but to try to convey to others (and to himself when he has occasion to refer to a previous judgement) the character of a particular wine. If wine-tasting possessed its own glossary of terms, with each word corresponding to a well-recognised sensory experience, there would doubtless be more science and less art in the work of keeping a record of different types and vintages. But, in the nature of things, this is impossible. Every tasting experience is unique and elusive, and the wine chronicler must perforce be something of a poet striving to express his inner feelings.

So much for the practical considerations; but it would be less than honest to pretend to justify the language of wine simply as a means of communicating information. Even were some zealous student of semantics to succeed in evolving a completely objective way of describing the qualities of wine, we doubt whether his bald symbols would find much acceptance amongst wine-lovers. For in the heady prose of wine literature there is a hint of mystery, a promise of escape from all things trite and dutiful, that would be sadly lacking in such a statement as: “Alcoholic strength, 20 Proof; taste range, :25 to L27; perfume, AB7; annual maturation, 3/8.” Speaking for ourselves, we trust that wine will continue to bring out the poet in its devotees and to inspire such phrases as that beloved of the late Mr. Francis Berry… “silky on the farewell.”

*Founded in the early 1920s in honour of the late Professor Saintsbury as a dining club representative of the wine trade and literary world. Today, with some 50 members, it is one of the few such clubs still flourishing and dines twice yearly in Vintners’ Hall.