Claret: The Wine of Infinite Variety

Author: Berry Bros. & Rudd

Since the days of the Black Prince, when Bordeaux and the neighbouring country were English territory, the people of these islands have cherished the fine red wines yielded by the stern soil and generous sunshine of that favoured region. Under the name of Claret (so used only in this country, though derived from the old French word meaning “pale and clear”) the red wines of Bordeaux have graced our taverns and tables for as many centuries as men have read Chaucer, inspiring the homage alike of Elizabethan courtier, Restoration wit, eighteenth-century essayist and Victorian novelist.

Claret has well deserved this place in our national life, for it is not only the most perfectly balanced and subtly flavoured of the world’s wines, but also – to quote André Simon – “the most natural and the most wholesome”. If Burgundy is the King of red wines, then Claret is surely the Queen – and many would make her Queen Regnant. In size of domain she is certainly pre-eminent, and for this reason it is impossible to do justice to Claret in a single article; to speak in the breath of the delicate wines of the Médoc, and the robust and Burgundian wines of St. Emilion, is necessarily only to skim the surface. Nevertheless there are some useful remarks that can be made about Claret as a whole by way of introduction – and this we propose to do here, leaving closer consideration of particular districts and growths to another occasion.

That great charm of Claret, its endless variety, is expressed not only in the types available but as much, or more, in the infinite shades of interest and excellence. At one end of the scale there are the superlative and expensive First Growths, such as Chateau Lafite and Chateau Margaux; at the other, the inexpensive vins ordinaries now available in England at 7/6 a bottle or less.

Both types admirably fill a need, but certainly do not exhaust the choice. Indeed, it may surprise some readers if we suggest that the most regarding category of Bordeaux wines – considered as value for money – are those described as bourgeois growths and those of the lower grades of classification. Available to the British consumer at about 10/- to 16/- a bottle, these are necessarily wines that have been shipped in cask for bottling in London and therefore have not the cachet of the famous First Growths, all of which have to be bottled at the Châteaux. But it must be remembered that wine of the Fourth or Fifth Growth of the Crûs Classés (the official 1855 classification of the great wines of the Médoc) is still amongst the leading clarets and the world’s finest wines. As for Château bottling, this is a question on which we feel very strongly and would like to say a few words.

A wine can be – and is – bottled every bit as well in the London cellars of a reputable wine merchant as on the estate in France; an experienced head cellarman over here has all the skill of his French counterpart. The difference in price is immediately evident, because the duty paid on wine imported in cask is very much less than when imported in bottle. That is the reason why the excellent Clarets listed on page 7 [see below], which have been selected with great care by both shipper and wine merchant, can be offered at such a reasonable figure. You can be sure that a wine on which an old-established London merchant is ready to stake his reputation possesses a cachet comparable with that of the Château-bottled product.

Although a natural variety of nuance is on o the charms of Claret, that does not mean that any part of its production can be left to chance’ on the contrary, immense labour and vigilance are demanded of the grower to ensure that conditions are as conducive as possible to the miracle which he hopes Nature will perform for him. It is a joyful yet anxious time in Bordeaux when the laden carts are bringing in the harvest and the air grows sweet with the scent of crushed grape. Much of the grower’s painstaking work in protecting his vines from disease, pest, frost and countless other perils would be undone if a downpour, for instance, were to wash away that host of microscopic organisms which has appeared so magically on the ripened grapeskins to promote natural fermentation. The maître de chai anxiously watches his precious harvest as the grapes are brought to the cuvier or pressoir, their stalks removed, and then crushed and passed into the fermentation vats.

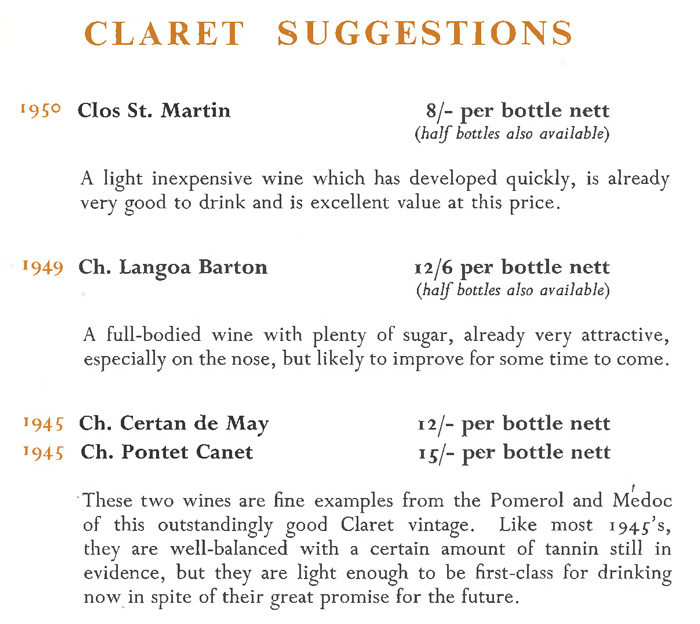

The slightest variation in conditions can so affect the grape itself or the process of fermentation that it is difficult to speak generally of any year’s vintage. The same type of vine may yield wine of distinctly varying character in neighbouring vineyards, and even adjacent rows. On this subject, therefore, we are confining ourselves to a few brief remarks about the character of those particular wines of ’45, ’49 and ’50 vintage suggested below.

The ‘45s are likely to keep longest by a considerable margin despite being the oldest’ although some are right to drink now, others are not yet ready. In the long run this vintage will, we think, have a greater reputation that the very attractive ‘47s, which are now so scarce. The young ‘49s of the cheaper and less distinguished class can be drunk with pleasure now’ the more expensive varieties not yet, but they can be depended on to turn out very well. This vintage is light attractive, sugary and developing quickly in bottle. The ‘50s have not such obvious attraction as the ‘49s, but are well-made, well-balanced wines which, being made in the first plentiful year since the war, have the great advantage of being available at low prices.